Chef in Residence Bryant Terry Presents Feeding the Resistance

Chef, author and food justice advocate Bryant Terry is a 2015 James Beard Foundation Leadership Award-winner renowned for his activism to create a healthy, just, and sustainable food system. He focuses on ways to increase access to healthy, affordable food. A lifelong learner and educator who leads by example, Terry offers practical advice about how to be mindful of ways to eat - and help others eat - differently.

Podcast Preview: Chef, author and food justice advocate Bryant Terry talks (vegan) turkey

Chef and activist Bryant Terry gets pragmatic about healthy eating and why access to healthy, affordable food is a social justice issue we all need to understand.

Transcript

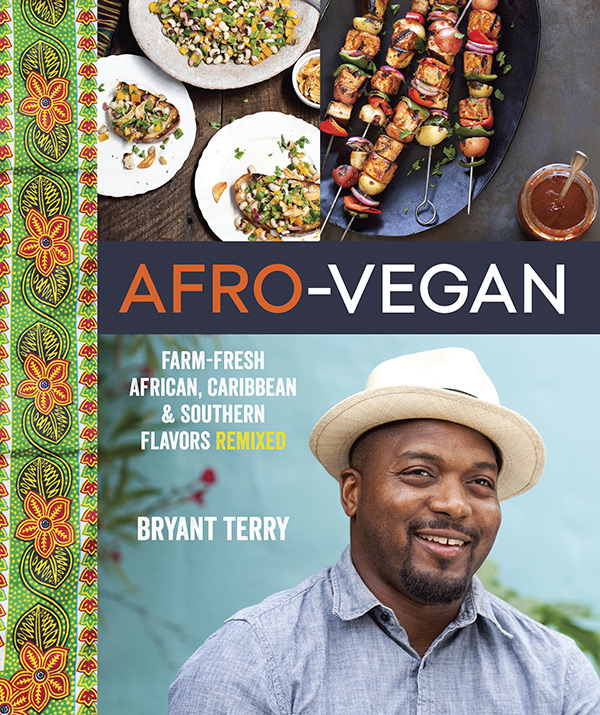

Megan Hayes: Chef, author and food justice advocate Bryant Terry is a 2015 James Beard Foundation Leadership award winner, renowned for his activism to create a healthy, just and sustainable food system. In particular, he focuses ways to increase access to healthy affordable food. Terry is the author of the critically acclaimed Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh Healthy and Creative African American Cuisine, which was named one of the best vegetarian/vegan cookbooks of the last 25 years by Cooking Light magazine. Terry's fourth book Afro-Vegan was published in April 2014. In December of that year, it was nominated for an NAACP Image Award in the Outstanding Literary Work category. A lifelong learner and educator who leads by example, Terry encourages others to always be mindful of ways to eat differently. Bryant Terry, welcome to Sound Affect.

Bryant Terry: Thank you for having me on.

MH: So glad to have you here today, so let's get started with a very basic question; what is a vegan?

BT: What is a vegan? A vegan is one who avoids any animal or animal derived products and if it were up to me I wouldn't put so much focus on vegan, my goal is to get people eating real food again, and I think the culprit which I think we all need to be aware of is this meat processed, package heavy, fatty diet that most Americans are eating and we're seeing the effects of, particularly here in the south. So I just want people to get back to eating real food and with the Afro-Vegan concept it's just celebrating the staples and flavor profiles and ingredients from the African continent, the Caribbean and the American South and really seeing those as something that can bring health and bring life and pleasure. So in general, my approach is, let me help educate consumers, eaters, Americans and others about what's happening in our industrialized food system and what's happening with factory farming, how that's impacting animals and the environment and local economies, how eating more local, seasonal and sustainable fresh whole foods can have such a positive impact on our own personal well-being, of communities, local economies and then let people make their own decisions and they have to live with that. I want to re-contextualize and help people reimagine these things as compassionate and fun and delicious and not heavy and overly political and self-righteous.

Transcript

Megan Hayes: Chef, author and food justice advocate Bryant Terry is a 2015 James Beard Foundation Leadership award winner, renowned for his activism to create a healthy, just and sustainable food system. In particular, he focuses ways to increase access to healthy affordable food. Born and raised in the southern U.S. he is currently the inaugural chef in residence at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, where he creates programming that celebrates the intersection of food, farming, health, activism, art, culture and the African Diaspora. Terry is the author of the critically acclaimed Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh Healthy and Creative African American Cuisine, which was named one of the best vegetarian/vegan cookbooks of the last 25 years by Cooking Light magazine. Terry authored The Inspired Vegan and coauthored Grub, which the New York Times called "ingenious." Terry also served as the humanities advisor on the Between Meals Cookbook Project, which shares the recipes, and stories of newly arrived refugee and immigrant women and explores how they have nourished their families in the United States. Terry's fourth book Afro-Vegan was published in April 2014. In December of that year, it was nominated for an NAACP Image Award in the Outstanding Literary Work category. Terry is the host of Urban Organic, a multi episode web series that he co-created and he was co-host of the public television series The Endless Feast. He also served as an expert on the Sundance Channel's original series Big Ideas for a Small Planet. He's also made dozens of national television and radio appearances including being a guest on The Martha Stewart Show, Emerald Green, All Things Considered, Morning Edition, The Splendid Table and The Tavis Smiley Show. A lifelong learner and educator who leads by example, Terry encourages others to always be mindful of ways to eat differently. Terry graduated from the Chef's Training program at the Natural Gourmet Institute for Health and Culinary Arts in New York City. He holds an MA in History from NYU and a BA with honors in English from Xavier University of Louisiana. He lives in Oakland, California with his wife and their two daughters. Bryant Terry, welcome to Sound Affect.

Bryant Terry: Thank you for having me on.

MH: So glad to have you here today, I want to get started with a very basic question; what is a vegan?

BT: What is a vegan? A vegan is one who avoids any animal or animal derived products and I feel like I need to say this upfront, for my body of work, for my mission in creating healthier communities, I've been very clear that eating more plant centered diets, or more whole food diets can be very effective in preventing chronic illnesses and helping to ameliorate symptoms and sometimes on some cases reversing chronic illnesses. If it were up to me I wouldn't put so much focus on vegan, my goal is to get people eating real food again. I think the culprit to this exponential rise in preventable diet related illnesses that we see in our country is directly related to the standard American diet, which is replete with a lot of processed and packaged food and far too much meat. I would like to see people eating fewer animal products. In some cases, I want people to be aware of the implications of eating animal products. There are a lot of arguments that I and many others could make about why we shouldn't eat animal products; environmental, economic, certainly ethical if we think about the horrible ways in which many animals are treated in our industrialized food system but, it gets tricky when we start talking about prescribing diets for better health. I think it's important to recognize that everyone is so different. Everyone's body constitutions are different, their bodily needs, their cultural food ways-- and so I really want people to consider all these factors when thinking about what's best for them to eat for better health and wellbeing and not think or imagine this panacea, whether it be vegetarian, vegan or raw food or whatever diet...whatever the new latest fad diet that will make you the healthiest and strongest is and just be thoughtful about what they're eating every day.

MH: So you present yourself as an Afro-Vegan; what does that mean exactly?

BT: I don't though, that's the thing. My publisher-- it's one of those tricky things where you work with a corporation that produces your work and they have certain ways of marketing it. I certainly don't have problems with it, I think a lot of people actually get excited when they hear that, but when we talk about this whole concept of Afro-Veganism, for me it's putting food of the African diaspora in the center of the conversation around eating healthful, specifically when we talk about communities of color and the fact that in the United States, and increasingly abroad, people of African descent are suffering from some of the highest rates of preventable diet related illnesses. One of the criteria that I always talk about is that eating your ancestral foods, the food that our grandparents were eating; how did they maintain these healthful lifestyles before these industrialized, sedentary lifestyles that we live today? So I just want people to get back to eating real food and with the Afro-Vegan concept it's just celebrating the staples and flavor profiles and ingredients from the African continent, the Caribbean and the American South and really seeing those as something that can bring health and bring life and pleasure to people's kitchens. Certainly I'm invested in more African Americans and other people of African descent eating these types of foods but I feel like these are types of foods that I want everyone to enjoy. When you think about the diverse food cultures throughout the African continent, the Caribbean and just diverse cultures of African American eating throughout the American south and increasingly throughout the country, the experience people spread through the Great Migration and other ways of taking those food cultures from the south and spreading them around the country--it's good food! Who doesn't like black-eyed peas and corn bread, a good mess of greens? That's the food that I and a lot of southerners grew up eating. I really want to push back against these stereotypes that African American food is all bad, artery clogging, unhealthy and the bane of the health of African Americans and other southerners. The culprit I think we all need to be aware of is this meat processed, package heavy, fatty diet that most Americans are eating and experiencing the effects of, particularly here in the south.

MH: So it sounds like you're not trying to convince people to necessarily become vegan?

BT: I just try to stay away from that. I think it just gets tricky. Before I thought about writing a book, before I started doing public speaking around these issues, I was working with young people in New York City. I founded an organization called Be Healthy and our goal was to politicize and enlighten young people around these complex food issues. Our approach then was that we wanted to give them the most information so that they can make informed decisions because we knew that they were getting so much of the corporate story. They were getting bombarded with ads and jingles and billboards and things that were convincing them to eat the worst foods; high in fat, high in salt, and high in sugar. You can't blame children or any individual when there's this bombardment with things telling them to eat the worst foods so our goal was to help them understand the negative impact that over consuming those types of foods had on their bodies and minds and spirits but also helping them understand the opposite; what happens when you eat more fresh food, when you eat more fruits and vegetables, eating fewer meat products and how that can have a positive impact in the body. So once we did that, we told that it was up to them, if they wanted to continue eating McDonalds every day, or drinking sodas every day, and eating a lot of processed and packaged food then they had to live with that decision. So in general, my approach is, let me help educate consumers, eaters, Americans and others about what's happening in our industrialized food system and what's happening with factory farming, how that's impacting animals and the environment and local economies, how eating more local, seasonal and sustainable fresh whole foods can have such a positive impact on your own personal well-being, of communities, local economies and then let people make their own decisions and they have to live with that. I think there's this stereotype that a lot of people have of the finger wagging, self-righteous, dogmatic, judgmental vegan, so there's always been this fine line of me presenting this information but trying not to fall into that way in which a lot of people imagine them because it turns people off. I think a lot of people have had such negative experiences with vegetarians and vegans who are proselytizing and attempting to get them to eating the way they think they should eat it becomes a matter of saying those words and having people turn the other way and run. I want to re-contextualize and help people reimagine these things as compassionate and fun and delicious and not heavy and overly political and self-righteous.

MH: Do you get feedback from people who feel like a vegan lifestyle diminishes nutrition? Maybe raising your children vegan and are worried that they are not getting enough protein or they might not grow up healthy.

BT: I hear that a lot. The thing is most often when I hear that argument it's coming from people who are adamant that a vegan diet is a bunch of crap. It is usually an argument that is used to undercut any kind uplifting of plant-based diet as something that can be helpful and beneficial. I do think that one might need to be a little more thoughtful in getting protein and micronutrients. I think in general because of our industrialized food system. The food that we grow is not as nutrient rich as it was forty or fifty years ago. I think we all should be considering the ways in which eating vegetables from the supermarket that have been shipped from California, as most food is, is going to be much less nutrient rich than food grown locally that's been harvested that morning or the day before. I think in general we need to be thinking about how our consumption decisions are impacting our health and all the other things talking about our local economy and supporting our neighbors. But if we are sticking to the conversation about what's most helpful people can eat a diet that has a lot of meat in it and it could be a very unhealthy diet. If you want to look at it as clean meat versus not clean meat. You could eat really horrible meat products that are not giving you the nutrient benefits you might get from meat that is cleaner. There are some vegans who might be listening to this and thinking how can you talk about meat in these ways? I feel like we need to understand the reality that they're some people who are not going to give up meat. I can use my parents as an example. I feel so good that they have made these small strides. They have read my books and watched films and read other books that I've recommended. They only shop at the farmers market primarily for their produce. They don't eat white sugar anymore and they try to have smaller portions sizes, but both of them are adamant that they like to eat meat. They don't do it as often, but they're going to occasionally do it. I try to help them find resources in their community where they can get meat that is "clean." I can be hardline and some people may see it as morally self-righteous to just talk about a plant-based diet or to just to promote a vegan diet, but I am a realist. I want everyone who eats to understand these complex issues and all the options that are out there. I just want people to have enough information to make the most informed decisions and they just have to live with the decisions they make.

MH: Talking about what is realistic. One of the things is that we are in the mountains, even though we are in the south, and we have these fantastic summers where you can grow things. But, there is a long period of time when you can't grow stuff. Our growing season is really short. What about the off-season? How are you going to eat fresh in February or March?

BT: Well you might not eat fresh, but we have to go back to the olden days and do it like grandma used to do. There is canning, pickling and preserving. They're so many ways in which the food from the bounty of the fall and summer are preserved so in those leaner months you can have a lot of food you can eat to create a diverse diet. You might not be able to get as much fresh food, but there are options of going to the conventional supermarket and getting food that has been shipped from other parts of the country. I think we have to get back in tune with the touch with the natural rhythm of the Earth. I believe that Mother Nature knows what we should be eating. Obviously in the summer time the Earth produces more watery fruits and vegetables. For example cucumbers and watermelons that are very hydrating. In the winter we are eating more grounding, warming and filling foods like tubers and root vegetables. In our industrialized food system you can get strawberries in the dead of winter or root vegetables in summer. You can get everything all the time and I think it is something to consider in terms of being mindful about what we are eating and getting back in tune with the rhythms of the earth. That means you might not be able to eat mangos in the dead of winter or strawberries. It gives you something to look forward to. Spring is coming and asparagus is going to appear soon or those fresh strawberries are going to be appearing in the next few months. I firmly believe that these practices like canning, pickling and preserving we need to revitalize them. We need to tap into this wisdom of our elders. They maintain those practices throughout their life and we need to learn them, reproduce them and teach them to the next generation.

MH: Let's talk about the history of the local food movement for a minute because I do think it may seem a little faddish to younger people. But, this has been around for a while… Do you think it is gaining more ground or having resurgence?

BT: The reality is that so much of my work is driven by memories of my own family having these practices. They didn't call it local food they didn't call it the organic local seasonal sustainable movement this is just the way that they lived. My family had farms in rural Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas. We had back yard gardens all the time in Memphis where I grew up. I think about my paternal grandfather: Andrew Johnson Terry he had an urban farm in his backyard. He literally used every bit of available space to grow food. He had pigs and chickens in the backyard and we are talking about a neighborhood adjacent to downtown Memphis, TN. Because of that, all of the grandkids, including myself, we had to be a part of the process of planting, growing and tending then also with the shelling and shucking which I used to hate. But I so appreciate that time and knowing that this is how that generation knew how to survive and he would talk about that. He wasn't a highly educated person, but he was so wise. He used to share so much knowledge and one thing he used to say to me often was that "you need to be equipped to grow your own food because if you depend on other people to feed you then as soon as they decide not to feed you, you are going to starve." I forget the question you asked me I feel like I'm just going on…

MH: No, it's about the importance of each person understanding the origin on his or her food culture. As you were saying that I was thinking about going to my great-grandfather's house and all of the family picking strawberries. It was this big thing where we would pick the strawberries and then hull them and then cut them. Then my grandmother would make tons and tons of strawberry jam. I hadn't even thought about that until you started saying that.

BT: Where I was going is that I think there is this collective amnesia that people have. When you said that you didn't even remember that. I feel like this industrialized food system facilitates people forgetting these practices and I always say the work that I am doing is standing on the shoulders of the many ancestors before me. Blood ancestors and spiritual ancestors that have been doing this work either intentionally as activist or just to build a thriving community. I want people to remember these things. When I give talks across the country one of the first things I do is ask "how many people had farms growing up or gardens? How many people canned, pickled and preserved? How many people made food from scratch and didn't cook it in the microwave?" Inevitably people are raising their hands and they totally forgot. "Nana had this garden or Memaw used to pickle" I just want people to remember that it is not that big of a stretch to think about eating and maintaining these practices. Just a few generations ago many people in our families maintained these practices. I think it is about talking to the elders and getting a good sense about what they did and honoring their hard work before we came.

MH: Do you think the act of acquiring, preparing and eating of local foods ties into social justice?

BT: I do. I often talk about the economic benefits of eating locally, seasonally and sustainably. When I was hosting a show on PBS "The Endless Feast" and we traveled around the country and talked to small farmers and independent artisans, these people who are producing food in beautiful and powerful ways. There was a grocery chain that was often implicated for cheating farmers. This corporation would buy their tomatoes at a very cheap price and they would go into the market and see them being sold five or six times the price that they sold them for. When I hear that it makes me think about the way in which supporting our local farmers at the farmer's market or local CSA or actually going to the rural farm.... They get so much more money from every dollar we spend. I think on average at the farmer's market the farmer gets ninety cents on every dollar that we spend. Whereas if you go to a supermarket the farmer is getting about ten cents to every dollar because of packaging, shipping and marketing. There are all these other external cost. Just the simple act of buying food locally is a way to support our neighbors who really care about us and who care about growing food with integrity and sustainably. It is hard because if you start talking about the economic and environmental benefits a lot of people will shut down. For me one of the reasons I started writing cookbooks is because starting with delicious food is such a powerful way to even move people towards the political, economic and environmental reasons. My guiding mantra has been to start with the visceral to ignite the cerebral and end with the political. I think seemingly apolitical acts such as growing food, making meal from scratch and building a community around the table can be a powerful bridge to get people to think about changing their own habits and politics about food. Also helping them become more active in transforming their communities. Starting with the politics and activism...I don't know if that is the most effective way. It was one of my critiques when I started this work in 2001. I was seeing a lot of people who care about these issues deeply who were misguided when they started with these things. That is a very activist approach and I think you need a very human approach to get people to think differently about food. That is just like feeding people.

MH: You know we've been talking about this issue as people who have choices. Food insecurity is a significant issue in North Carolina and in our county, 2014 data show that 25% of our state's citizens face food insecurity. Nearly 1 in 5 face the same challenges in Watauga County, which is where we are. Eating local can be more expensive in terms of time and/or money. So what solutions are there to increase access to healthy food for people who might be choosing to spend money on food or spending money or medicine? Or heat?

BT: I could give you my kind of larger, philosophical answer about the way in which we need to fundamentally question capitalism. We need to think about the ways in which wage, inequality and the lack of jobs and all these things impact people's abilities to take care of themselves and their families. I understand the reality of a young single mom who has to work two or three jobs just to put food on the table. Then we need to think about, why is it that wages are so low? Especially when the corporations that are often paying these pittance wages are some of the wealthiest corporations in the world. Their CEOs are getting paid billions of dollars; the CEO is getting paid 300 times what the actual workers are getting paid. I think we have to question those things. I think it's a Band-Aid solution to if we think about fixing these problems without getting to the core problems of capitalism and the ways in which it creates inequality and how the wealthy 1%, the people who are running the corporation, the people who are owning are making a lot of money and the people who are actually running the corporation because they are the workers and they are putting in their labor, aren't getting paid what they should be.

So I say that to say that understanding the structural inequality that prevents people from having access to healthy fresh and affordable food makes me, and I think it should make most people, compassionate and not judgmental. I see a lot of food shaming and judging of poor people. I think that's a huge problem because it fails to recognize these structural inequalities. So if a young single mom is going to McDonald's and getting food from the dollar menu, of course I am aware of how unhealthy that can be and how unsustainable that can be for her, but who am I to judge? Because I understand the situation that they are in and I think that in order for us to address these problems on the ground level, we have to get out of this capitalistic mindset that I need to address every single problem by myself. I think that we need to have collective action with all these different stakeholders in the community, especially the ones that claim to care about the community. I will give you an example. I think about churches, faith based institutions. I don't know if you've ever been to a church, but I've been to churches across the country that have these fantastic industrial kitchens that are sitting there just dormant for like two decades. You go in there and there are cobwebs, clearly it has not been used. So I think about something like that and I think, what if the preacher or reverend or the spiritual leader of that institution decides that in additional to spiritual subsistence, they are going to have a keen focus on improving the physical health and well being of their members. What if we revitalized this kitchen? What if we open it up and we use it as a space to incubate small food businesses? What if we used it as a space where we have elders in the community coming in and passing down these traditions like how to can and pickle the preserves or how to make food from scratch? What if this same church that has this huge plot of land that is being underutilized or not being used at all, what if you converted into a community garden or open farm? Then they are actually growing food that we can give away to the members of the church? Then what if on Saturday, fifteen people in the church going out to the Farmer's Market and buying all this food in bulk? Then you come back to the church and then you make a big pot of stew and I make a casserole and someone else makes some pasta. Then we all have these collectively made, healthy fresh foods that we can divvy among the group and share throughout the week. So that's just one example of the way that I think that people could come together collectively, facilitated by these institutions and communities and actually, help each other to eat more healthy. Help each other to have fresh foods. Help each other to feed their families. I just want to see more institutions that claim to care about communities being active in this movement around healing communities, around healing people, around building a healthier and more sustainable food system.

MH: Yeah related to this, there is a large portion of our community that is on free or reduced school lunches. This is a big challenge for school systems and this is my big beef is just the school lunch and my personal vendetta against the school lunches. I spoke with one our school board members about this and he said that the biggest challenge is how do they purchase food in mass quantities because really they have pennies to spend on lunches per meal. So even when there is a lot of momentum across the country supporting local food and we have people right here who are growing it, it can be cost prohibitive. How do we solve that? Have you seen this in other areas of the country? Have you seen solutions to it?

BT: Well, I will first say that when I started doing this work back in 2001 I give that the two sites that could be most powerful in transforming our food system would be faith institutions and schools. And the two sites that gave me the most resistance have been faith institutions and schools. It was really sad because it really turned me off from doing work with schools. I understand the bureaucracy and why it's so challenging to move this huge ship in a different direction. Things are changing; I mean that was a long time ago. We've seen the Farm to School movement has completely shifted. There are a lot of really powerful models across the country. I think about one, a lot of people know about, The Edible Schoolyard in Berkeley, California. The whole school has thought about how they collectively can work towards feeding their children better. You know, they have this amazing garden; they have kitchen staff that is actually using food from the edible garden. They make fresher foods, they have a salad bar. All that to say there are some models out there. We need to also think about the practical issue of where we are going to get the money. Once again, we need to think about these issues around inequality. Why is it that we can't find enough money to prioritize feeding our children well, but yet our defense budget is enormous? As much as this country claims to care about children, we need to see some action. We need to see some priority shifting where we can put more money into feeding our children healthful good food...real food. At the end of the day if we want to see this whole system be sustained, we have to invest in children. There is growing research that connects nutritious foods with academic achievement, with good behavior and just the ability to just be still and pay attention. I think that there needs to be a shift in priorities so that we can actually find ways, creatively find ways. I've seen it happen. School districts need to be very creative. Fundraising outside the school and reaching out to experts in the community to help with these efforts, such as master gardeners and different chefs within the community. It may require people volunteering time, but again how can we come together as a community and be part of this movement to feed our children better and create healthier food systems? I kind of broached it, but I feel like I just have to say this. If we want to transform our food system, we need to think about ways that we can be active - not just as individual consumers. I think it's important that we understand every dollar we spend is a vote for the type of food system we want to see. However, the reality is that consumer change is simply not enough to transform our food system wholesale. We need to be activist consumers, but also we need to be activist community members. That's what we were talking about for the last couple of minutes. How can we as community members, as stakeholders and different organizations come together and work towards transforming our food system? We need to be activist citizens. We need to vote with our vote. We need to ensure that we are putting elected official into office on the federal level, state level and local level who care about these issues; who truly get it. Who truly get understand the dire need to shift our priorities who will work towards healthier foods systems, healthier communities and ensuring that our children and grandchildren actually have healthier lives and have a longer lifespan than our parent's generation. Another thing that troubles me is that this generation of young people is at risk for having a shorter lifespan than their parent's generation. That's just not right. With as many technological advances that we have and as many resources that we have, these children should be living longer and healthier lives than us and that's just not the case.

MH: I've heard you talking about how important it is to make policy changes to combat nutrition issues. What does that look like to you?

BT: I think it looks like...that we have a presidential election coming up and I think it's important to think about what candidate is reflecting their values and ensuring all that they can to put that person in office. But I think that you get a lot of bang for your buck investing time in local elections. Doing things like creating food policy councils and changing laws in local areas. I don't know what a lot of the restrictions are around urban home steading and towards growing food are in this area, but you know just little things that can actually facilitate people eating healthier. Or having more local food system support for small farmers. We know that many of the subsidies are going towards the wealthier agricultural organizations. Then you have small independent hardworking good family farmers who can barely survive and have to take jobs outside of their job of farming just to keep their family afloat. Why can't small farmers get some subsidies too? Why can't we help them to be as sustainable as we are doing for these big wealthy corporations? Helping minority farmers, by minority farmers I mean not just white male farmers such as women farmers, many of the African American farmers who have suffered decades of discrimination, often times by the USDA. So there are ways in which our government could be very active in creating a healthier and just food systems simply through policy changes and that has to come through us. That's why I always talk about people power, grassroots activism, because ultimately with all these institutions the people are the ones in charge. I think people get it confused and they think, "well you know it's the preacher up there." But no. Without us, without the people in the pews, the preacher wouldn't have any power at all. We need to make demands so they can guide institutional change. We need to understand that those people are in office because we put them there and if they aren't making decisions that are in our best interest we need to kick them. Put someone else in the office that will actually be making decisions in our best interests. So it's all about people power.

MH: One thing I think is very interesting is the work that you do that is about the diaspora and, particularly as a descendent of an Appalachian or of Appalachia, there's this kind of…I'm interested in the concept cultural appropriation, particularly when it comes to food. Appalachian food becomes a fad every so often and I think it's experiencing resurgence. There are these upscale urban restaurants that have taken on the Appalachian culture and one of things that I have heard is that instead of the food leaving our region is perhaps we should be bringing people to our region to experience the food. To experience the food. So do you see the value in food leaving or people coming to a region to experience that food? I'm just interested in your thoughts on location-based food in its authentic setting.

BT: I am not totally against different regional and cultural foods being celebrated outside of that context because I would expect for a chef who was born and bred in Appalachia, for example, and moved to another geographic location celebrate their cultural food and to help uplift those roots. I think that the issue I have is whether we are talking about is whether regional food ways or cultural food is this phenomenon that we see here is that white males who have the privilege of going to culinary school or have the access to capital to start businesses who will make these foods and make a lot of money off of these regional or cultural floodways. They may not necessarily come from those regions or cultures. They may not necessarily have a genuine respect for the people from those regions and cultures. That's where it gets thorny for me. When you take these traditions that people have maintained and worked hard to sustain over generations and then take it out of their context as means to purely generate profit, I think that's when things get tricky. I just wanted to say before I forget, you were talking about what is happening in Appalachia and I feel like I have to say this. My work has been focused on issues that people are dealing with in cities and in urban centers and those people are most often low income people of color, but I want to bridge those gaps and show that the same types of food insecurity that low people of color are dealing with in cities you often have poor white people in Appalachia dealing with similar issues around food insecurities and similar issues are around these preventable diet related illnesses. I just think that there is opportunity for collaboration. A lot of rhetoric that we have seen in this current election has been very divisive and illuminating differences, but I think that often times there are so many things we have in common with people who live thousands of miles away from us. I think that recognizing and understanding these differences can be a part of healing and helping people understand that we are not that different. No matter what our skin color is or where our geographic location is. For me, I have focused a lot on the issues that pertain to people of color because I am an African-American man, but at the end of the day I am invested in healing the planet for everyone. I am invested in creating healthy foods for everyone. I am just a humanitarian. I love everyone. I want people to have the best in life. No matter where one lives or what color one is, I want people to have the best that we all should have of what's available to us. That's how I want to end it.

MH: That's wonderful. Bryant Terry, it has been my distinct pleasure in speaking with you today I think your thoughts on activism and really your thoughts about bringing people together in a community. Food is such a common denominator when it comes to creating community and I really look forward to everything you are going to be doing on our campus for the next few days. I also hope that you coming here will allow for your presence to last a little while longer on our campus. So thank you for joining us here in the studio today, I really appreciate it.

BT: I'm so happy to be here and I'm so happy to hear that people enjoyed my food.

MH: Oh it was fantastic, fantastic! I'm going back get a piece of that chocolate cake to take back to my dad.

BT: There you go

MH: Thank you

BT: Thank you

By Bryant Terry

2014

Podcast Preview: Chef, author and food justice advocate Bryant Terry talks (vegan) turkey

Chef and activist Bryant Terry gets pragmatic about healthy eating and why access to healthy, affordable food is a social justice issue we all need to understand.

Transcript

Megan Hayes: Chef, author and food justice advocate Bryant Terry is a 2015 James Beard Foundation Leadership award winner, renowned for his activism to create a healthy, just and sustainable food system. In particular, he focuses ways to increase access to healthy affordable food. Terry is the author of the critically acclaimed Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh Healthy and Creative African American Cuisine, which was named one of the best vegetarian/vegan cookbooks of the last 25 years by Cooking Light magazine. Terry's fourth book Afro-Vegan was published in April 2014. In December of that year, it was nominated for an NAACP Image Award in the Outstanding Literary Work category. A lifelong learner and educator who leads by example, Terry encourages others to always be mindful of ways to eat differently. Bryant Terry, welcome to Sound Affect.

Bryant Terry: Thank you for having me on.

MH: So glad to have you here today, so let's get started with a very basic question; what is a vegan?

BT: What is a vegan? A vegan is one who avoids any animal or animal derived products and if it were up to me I wouldn't put so much focus on vegan, my goal is to get people eating real food again, and I think the culprit which I think we all need to be aware of is this meat processed, package heavy, fatty diet that most Americans are eating and we're seeing the effects of, particularly here in the south. So I just want people to get back to eating real food and with the Afro-Vegan concept it's just celebrating the staples and flavor profiles and ingredients from the African continent, the Caribbean and the American South and really seeing those as something that can bring health and bring life and pleasure. So in general, my approach is, let me help educate consumers, eaters, Americans and others about what's happening in our industrialized food system and what's happening with factory farming, how that's impacting animals and the environment and local economies, how eating more local, seasonal and sustainable fresh whole foods can have such a positive impact on our own personal well-being, of communities, local economies and then let people make their own decisions and they have to live with that. I want to re-contextualize and help people reimagine these things as compassionate and fun and delicious and not heavy and overly political and self-righteous.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

Conversations with smart people about stuff that affects our world, and how we affect it

About Appalachian State University

As the premier public undergraduate institution in the Southeast, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives as global citizens who understand and engage their responsibilities in creating a sustainable future for all. The Appalachian Experience promotes a spirit of inclusion that brings people together in inspiring ways to acquire and create knowledge, to grow holistically, to act with passion and determination, and to embrace diversity and difference. Located in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Appalachian is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System. Appalachian enrolls nearly 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and graduate majors.

forrestertakedent.blogspot.com

Source: https://today.appstate.edu/2016/11/14/terry

0 Response to "Chef in Residence Bryant Terry Presents Feeding the Resistance"

Post a Comment